About an hour into “Bobbi Jene” —director Elvira Lind’s winner of the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival’s Best Documentary award, the audience is presented with the mission statement of its subject, dancer Bobbi Jene Smith. In an interview with a journalist, she explains that —in her craft—she seeks ‘a place where I have no strength to hide anything.’ Lind’s masterful film firmly situates Smith in this place regardless of whether she is on or off the dance floor.

About an hour into “Bobbi Jene” —director Elvira Lind’s winner of the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival’s Best Documentary award, the audience is presented with the mission statement of its subject, dancer Bobbi Jene Smith. In an interview with a journalist, she explains that —in her craft—she seeks ‘a place where I have no strength to hide anything.’ Lind’s masterful film firmly situates Smith in this place regardless of whether she is on or off the dance floor.

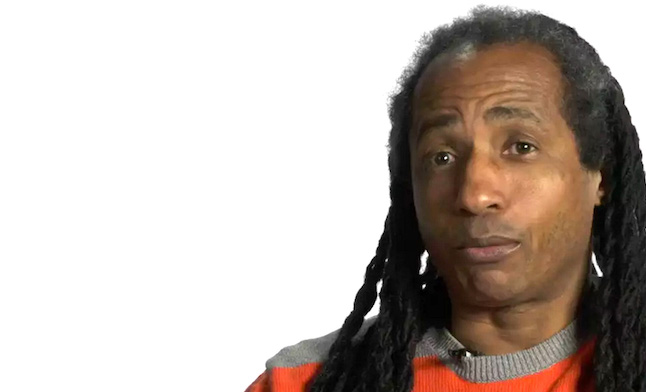

After quickly detailing the 21 year-old Smith’s earlier relocation from New York City to Tel Aviv to perform with the Batsheva Dance Company, the film begins with the now 30 year-old dancer returning to the United States. From the first shots, Smith’s face conveys a quiet, simmering intelligence that —coupled with the raw physicality of her dancing— demands attention. We often see her dancing in a frenzied state, her long hair billowing as she swings her arms upward and downward. Her performances sometimes end with contemplative stares into the distance, and her intense control is such that the viewer is left wondering whether these moments are genuine or part of the choreography.

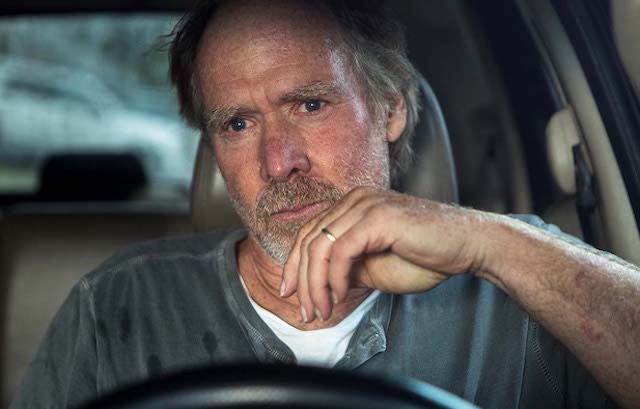

The film’s editing by Adam Nielsen was awarded at Tribeca, and it truly shines during one-on-one conversations. Nielsen is unafraid to let these two shots linger a beat or two longer than would be comfortable. In a conversation with her mentor Ohan Naharin (who was recently profiled in Tomer Heymann’s documentary “Mr. Gaga”), Smith mentions that she and her 20 year-old boyfriend Or hope to maintain a long-distance relationship while she is in the United States and he remains in Israel. Surprised by this news, Naharin —a former lover of Smith’s— asks, “Really?” Smith responds with a simple, “Uh-huh,” and Nielsen forces the audience to marinate in the palpable disquiet. In this and other parts of the film, the editor’s insistence on letting an uncomfortable scene breathe further exposes the wounds that Smith lays bare in her art.

Lind’s camerawork —which likewise won Tribeca’s cinematography prize in the documentary category— amplifies the vulnerability unearthed in Smith’s performances. Long shots show the dancer raging through the aforementioned routine in a spare, fluorescent-lit studio or aggressively struggling against the wall of a handball court. The dancer’s fury is marginalized in a small portion of the screen, dwarfed by the immensity of her surroundings. She appears to be at the mercy of an indifferent environment. Lind smartly frames Smith in ways that turn her dances into struggles against immovable objects, actively illustrating the ferocity with which she erodes the barriers between herself and her audience.

Focusing on a dancer’s self-discovery after leaving an adopted homeland appears at first glance to retread ground already covered by “Dancer,” Steven Cantor’s 2016 documentary about bad boy ballerina Sergei Polunin. However, Lind improves upon Dancer’s primary reliance on interviews and archival material with simple footage of Smith rehearsing and performing her choreography. In “Bobbi Jene,” Lind’s most powerful tool for portraying the life of a dancer is dance itself, lensed and assembled in a way that cuts to the core of the artist’s interior life.