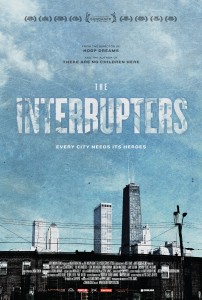

For Steve James’ latest documentary, “The Interrupters”, the director and author Alex Kotlowitz (There Are No Children Here: The Story of Two Boys Growing Up in the Other America) spent a year following Eddie Bocanegra, Ameena Matthews and Ricardo “Cobe” Williams, three former gang members who have committed their lives to “interrupting” violence on the streets of a Chicago neighborhood.. Like in his prior films, including “Stevie”, “Joe and Max” and the universally acclaimed “Hoop Dreams”, James follows close to his subjects while keeping any agenda at a distance. The film has its share of dramatic moments, but in the end it is about redemption and love.

Adam Schartoff: Did you always want to be a filmmaker?

Steve James: No, I wanted to be a pro basketball player.

Schartoff: “Hoop Dreams” was a result of that, I suspect?

James: It was very personal for me. When I was in college and it was clear that wasn’t going to happen, I ended up in radio journalism. There was an NPR station there and I thought that would be kind of cool. Then during my senior year in college, I took a film appreciation class and I fell in love with film.

Schartoff: Were there any particular documentary filmmakers that you were inspired by?

Schartoff: Were there any particular documentary filmmakers that you were inspired by?

James: I didn’t get into documentaries until I went and got an MFA in film. They didn’t have an undergraduate program (in film) where I went so I started taking some classes. I ended up just getting a degree. It was there, at Southern Illinois University, where I fell in love with documentary filmmaking. My teacher was very influential and it plugged into that radio journalist in me.

I love stories and it’s reflected in the documentaries I make. I wouldn’t make an Inside Job because I’m just more interested in following stories. It’s one of the reasons I don’t use experts. I want those people who are living in the world, the one I am filming, to be the experts. I’m more interested in what Ameena has to say than a sociologist who might have some brilliant things to say, by the way.

Schartoff: They are personal stories where you follow people over extended periods of time.

James: “Hoop Dreams” took four and a half years. I’ve actually been crazy enough to make two other films where we’ve followed people over periods of time. Over four years for one, and two years for another. I’ve got problems is what I’m saying. [laughs]

Schartoff: Also, there aren’t any theories that need to be proven for the films’ sake.

James: My movies aren’t polemical. But, and this is apropos of who you write for, they have a point of view. “Interrupters” has a point of view, as does “Hoop Dreams”, and “Stevie”. But the point of view isn’t prescriptive, as in this needs to happen at the end of a “participant” film, where they lay it out for you. I like to think that my movies leave room for you, as a viewer, to have your own ideas. You can get the point of view of the film and even disagree with it. I like films that aren’t so black and white, but are in the grey zone. [laughs]

Schartoff: Did you get a sense that Capricia’s story was going to emerge as a central part of the film while you were filming?

James: Yes. One of the things we worried about going in was, unlike “Hoop Dreams” or Alex Kotlowitz’s book, we had no central narrative to follow. We weren’t following some kids who aspired to play in the NBA. No built-in narrative arc, right? So that was definitely a source of concern.

Fairly early on, we landed on the idea to do a year in the streets with these interrupters. And along the way, we’ll follow them and see them do their job, and we’ll reveal who they were. And this is what happens in the movie. What we weren’t sure about until it happened, we didn’t know that the best interruptions go beyond the moment, beyond that moment of just stopping a potentially violent encounter. It really takes more than that, if you’re really going to change someone and get them on a different path. You have to follow up. As that became clearer, we realized that we have to show that.

Schartoff: So, it’s more than showing an incident, it’s a pattern.

James: It’s the philosophy realized. Like Eddie says: “Well, I stopped two guys from killing each other today, but what about tomorrow?” He asks in the film if he had really done anything. And it’s what you see with these three interrupters when they’re doing their work. In essence, it’s more than interrupting a moment, it’s about interrupting lives.

With Capricia, we thought her story was over at the nail salon. Ameena meets Capricia at this mediation, they bond, Capricia goes to the jail, she comes out and they go to the nail salon where Capricia has a breakthrough. To me it was this beautiful scene with Ameena telling Capricia she has a right to be happy. I came out of shooting that and I was, like, “Wow, she’s on her way.” But then this is real life…

Schartoff: You thought you had your cinematic arc, but life is messy and chaotic.

James: Right. If we were making “Precious”, that’s where it would have ended. And you would have felt satisfied. You know, if you had never seen Capricia again, I don’t think you would’ve felt cheated. But it would have been wrong to have ended her story there, given what subsequently happened.

Schartoff: The question of your safety while making “The Interrupters” comes up often during Q&As and interviews. As I watched the film, I never felt that particular tension, that the crew was in any danger.

James: Yes, their conflicts were not with us. They were with each other.

Schartoff: Questions like those are sometimes the result of stereotypes about the inner city. Were these stereotypes something you were conscious of while you were making “The Interrupters”? You could say the same thing about “Hoop Dreams”, as well.

James: Absolutely. I fall victim to stereotypes just like everyone else. I think I’ve learned that lesson in some fashion on every film I’ve made. In other words, I’ve entered in with certain ideas, stereotypes or notions that have ultimately been upended. That’s a reason alone to make films — for yourself and then, by extension, for your audience.

This may sound really Zen-like, but I do think when a film really works for an audience, it is essentially a distillation of the path that we, as filmmakers, traveled in the course of making the movie. It’s not as though we are turning the cameras on ourselves and saying, “Today we did this and it really bothered me,” or what have you. It’s not that self-referential or self-reflexive. But you’ve gone through this journey of discovery. When you make films like mine, you don’t start with a script, you start with an idea. If you’re true to the experience, you simply let it take you where it takes you.

That’s why in “The Interrupters”, it was purposeful that the very first crisis you see in the streets was not only one of the most vivid, if not the most vivid encounter, but we wanted it to knock people back on their heels. We wanted the reaction to be, “Who are these people? Oh my God, this is way out of control!” We wanted to slowly show how someone gets to be in that place in their lives. That’s essentially the same journey we went on when we made the film.

Schartoff: I was wondering how much you get emotionally involved and how it is to let go at the end.

James: In the case of “Hoop Dreams”, I’ve stayed close to William (Gates) especially, but I only see him a few times a year at most. He’s got a life to live and so do I. He’s got a career. I’ve got a career. So, the intensity of that beautiful experience that filming can be, and sometimes it’s not that beautiful, the relationships will change. You can say it won’t, but the reality is it always does.

“The Interrupters” opens in New York City this weekend and other cities later this summer. Check the Kartemquin Films website for screening updates, and keep up with documentary news and more on POV’s Facebook page.

[Article originally appeared: http://www.pbs.org/pov/blog/2011/07/the_interrupters_steve_james_chicago_violence.php]